Hamid Mir

In the early hours of April 10, Imran Khan became the first prime minister in the history of Pakistan to lose office through a parliamentary no-confidence vote. Khan had spent days trying to forestall the vote with a series of Machiavellian moves. On April 3, as soon as it became clear that lawmakers were prepared to oust him, he tried dissolving the national assembly in what some have called a “civilian coup.” But it didn’t work. In the days that followed, the supreme court foiled this attempt by restoring the assembly and ordering a fresh no-confidence vote, which finally led to his downfall.

Khan is not gone for good, of course. If anyone doubted it before, this episode shows that he’ll go to just about any lengths to hold on to power. He tried every trick in the book to keep himself in office, but it turned out that he had alienated too many key players (including many members of his own party). His refusal to step down triggered a full-blown constitutional crisis. And when the supreme court refused to play along, essentially forcing him to go, he ordered more than 120 members of his party not just to act as the opposition in Parliament but to resign from it altogether — a shameless act of contempt for democratic procedure.

And throughout it all, he resorted to a tactic that he has long used to discredit his critics: he accused the United States of conspiring against him — without ever producing anything in the way of evidence. In the months to come, as Khan and his followers do their best to undermine the new government of Shehbaz Sharif, we can expect him to take his populist rhetoric about foreign plots to the extreme.

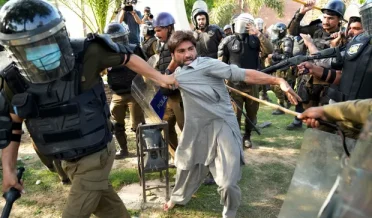

Khan announced a “freedom struggle” against alleged foreign meddling the day he lost office. He is planning to start a series of street rallies on April 13. He and his supporters never mention the failure of Khan’s long-repeated promises to reform Pakistani institutions and combat corruption; they almost never address the country’s dire economic situation, which is the direct result of his mismanagement and incompetence. Instead they endlessly repeat a single claim: All of Khan’s opponents are traitors, and they are all part of a U.S. conspiracy to bring about regime change.

Khan claims that he learned about the foreign conspiracy on March 7 from a letter sent by a Pakistani diplomat. This diplomat allegedly conveyed a threat from U.S. diplomat Donald Lu to the Pakistani government. This is nonsense. I wrote in January that Khan’s government was heading for a major crisis — one entirely of his own making. His enemies didn’t need any help from abroad to orchestrate his downfall.

In his first speech after becoming prime minister, Sharif told Parliament that he will convene a meeting of the national security committee as soon as possible. He will ask all stakeholders to produce evidence about the foreign conspiracy (including the mysterious Pakistani diplomat). If the allegations are proved true, Sharif said, he will resign from office.

Sharif’s hard-hitting speech struck a major blow to Khan’s conspiracy narrative. The security agencies already completed their investigation into the alleged foreign plot many days ago and informed Khan that there was no evidence. Rather than move on, though, Khan tried to make a deal with the head of the army to keep himself in power. He offered to keep Gen. Qamar Javed Bajwa in office indefinitely in return for the army’s support. But the general declined.

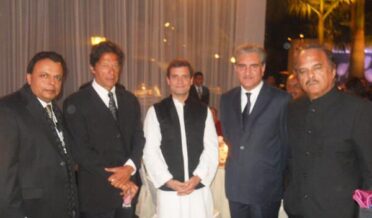

Political analysts have poked many holes in Khan’s claims. Former president Asif Ali Zardari and former prime minister Nawaz Sharif were responsible for arranging a massive influx of Chinese investment into Pakistan ― so why did the CIA never conspire against them? The United States has huge influence over the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. If the CIA was planning to overthrow the Pakistani government in March, then why would the IMF disburse $1.053 billion to Pakistan in February, and the World Bank $529 million in the same month? If Khan had received a threat from the United States on March 7, why did he invite a top U.S. official to the Organization of Islamic Cooperation conference in Islamabad on March 21?

On one side Khan is peddling a foreign conspiracy theory; on the other, Khan doesn’t seem to have any problem accepting the support of British politician Zac Goldsmith, his former brother-in-law. When Goldsmith was running to be mayor of London in 2016 against a Briton of Pakistani descent, Khan supported Goldsmith instead. Goldsmith lost to Sadiq Khan, who later accused Imran Khan of supporting a person who used racist and Islamophobic tactics against him.

Shehbaz Sharif must realize that he is not facing an ordinary politician. He must understand that his opponent is a ruthless intriguer who will stop at nothing. One can only hope that Sharif is up to the task.