Labour will have to think big to dig it out

Owen Jones

Nearly 30% of all Britain’s post-war prime ministers will have been in office in the past six years, all from the same party. But the cause of this chronic political instability is not just Tory psychodrama: it’s an economic model that has failed to deliver rising living standards.

David Cameron’s political career was consumed by a referendum result in which resentment over stagnating incomes played a key role: as one detailed academic study found, “Dissatisfaction over austerity measures was significant enough to give the leave campaign its majority.” When Theresa May’s premiership was fatally wounded by the snap election of 2017, voters’ rage at years of financial struggle – and a belief that Labour was best placed to do something about it – proved pivotal. While Boris Johnson was felled by deceit over illicit partying, public anger at an escalating cost of living crisis – and the Tories’ failure to address it – was crucial in suppressing Tory polling, leading his MPs to conclude he was no longer an electoral asset and could therefore be discarded. As for Liz Truss: well, no further explanation is necessary.

Even before the surge in inflation and Truss’s move to crash the British economy with a series of lethal right-wing policies, wages were set to be lower in 2026 than back in 2008. There was once talk of the financial crash and the subsequent Tory austerity triggering a lost decade in people’s living standards, but the reality we now face is a lost generation. Too often, political reporting reduces British politics to soap opera, to personality-driven machinations: to do so strips away the much more profound drivers of political turmoil.

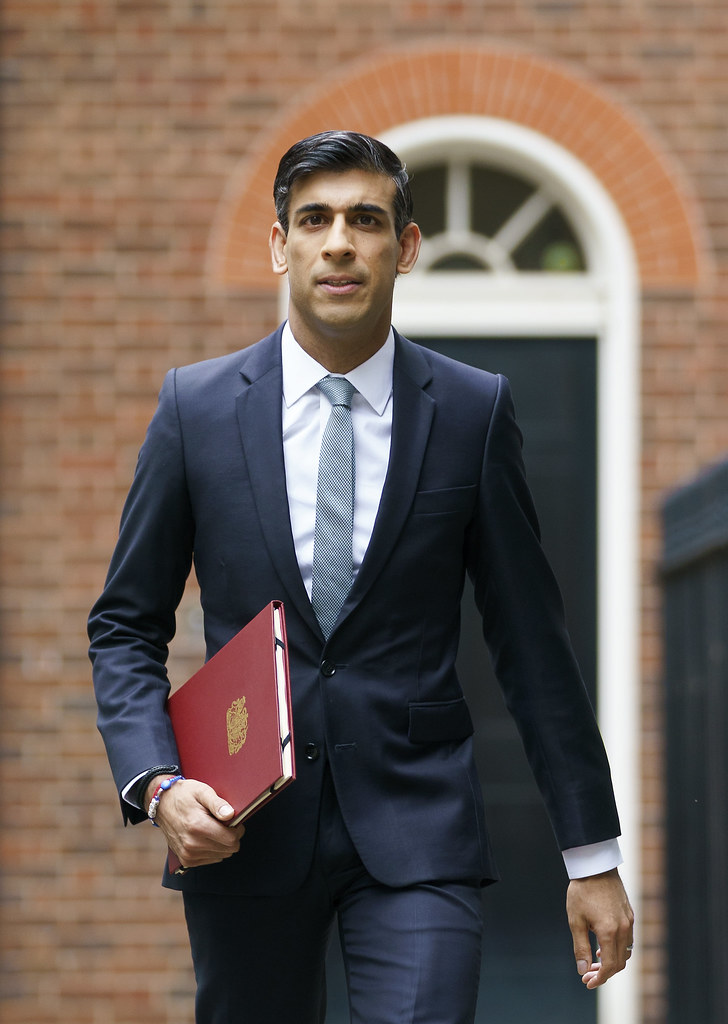

What, then, does the ascent of Rishi Sunak mean for all this? That he has been widely painted as a relative Tory moderate is a political travesty: Sunak is easily to the right of Johnson on economic policy. The anonymous briefing of one senior Sunak ally underlined why so many Tory MPs were uneasy with Johnson, and it wasn’t because of his addiction to deceit: “There is no evidence that during his time as prime minister he grasped the need for restraint in spending or had any understanding of how the public finances worked.” Johnson, they believed, was opposed to a renewed bout of austerity and lacked a true-blue ideological commitment to rolling back the frontiers of the state. Sunak, on the other hand, will gleefully wield the scalpel, from real terms pay cuts for the key workers who were hypocritically applauded by Tory ministers in the pandemic, to the core services that a healthy society depends on to function. Sunak must believe that he will escape the same fate as his four predecessors – three of whom were more experienced than him – even as he is likely to oversee a more dramatic plunge in living standards than any of them.

Sunak is likely to be the fifth and final Tory prime minister of this era whose career will end in humiliating failure, in his case an electoral rout at the hands of the Labour party will probably be his final chapter. As far as many of Keir Starmer’s cheerleaders are concerned, this will mark the end of Britain’s Age of Chaos. The post-2016 turmoil, they believe, was driven by the Tories’ infantile ideological zeal: now a supposed “pragmatist” and “grownup” will be running the show, and so stability will return, and politics will become boring again.

Labour’s rhetoric is about “sound money”, “tough choices” and “balancing the books”, and the fear must be that this will translate into austerity, albeit with a Labour rosette attached to it. If so, do not expect political turmoil to abate – quite the contrary. This would be unlike the New Labour period – after all, Tony Blair’s landslide was in the context of surging economic growth and rising living standards, hence the Tory slogan: “Britain’s booming: don’t let Labour ruin it.” This proved to be driven by an unsustainable financial bubble, but it bought a long period of relative social peace. If Labour comes to power in an age of acute social crises and fails to offer transformative policies to deal with them – and even relies on cuts – then more political tumult beckons, as Ramsay MacDonald’s and James Callaghan’s governments discovered in the 1930s and 1970s respectively.

The obvious response here relies on a regurgitation of Margaret Thatcher’s “There is no alternative”: that as Truss’ government was crushed by a market revolt over uncoated tax cuts for the rich, a Starmer administration wedded to unfunded public spending will suffer the same fate. But what it really means is Labour must commit to sweeping tax rises for Britain’s thriving rich to support ambitious spending commitments. It is notable that the markets were convulsed by plans to scrap tax hikes on big business: increases in corporation tax can now objectively be described as “market-friendly”. If advance briefings about Jeremy Hunt’s upcoming Halloween budget are to be believed, even the Tories are now examining the case for wealth taxes.

That gives Labour space to offer far more ambitious proposals. There is already a ready-made blueprint, developed by tax experts in 2020: a one-off wealth tax on millionaire couples paid at 1% a year for five years, they found, would raise more than £260bn. One of the architects was a tax expert whose job was to help wealthy clients navigate around tax law; their entire plan was developed by trying to prevent the rich seeking out loopholes. Should Labour, in two years, finally bring Tory turmoil to an end, it will face a choice: impose real terms cuts and provoke further chaos; increase public spending without proper costing and suffer market retribution; or address the country’s multiple social disasters with game-changing policies funded by tax hikes on those who have profited from these 14 bleak years. To coin a phrase, there really is no alternative.

Owen Jones is a Guardian columnist