Nisar Ahmad

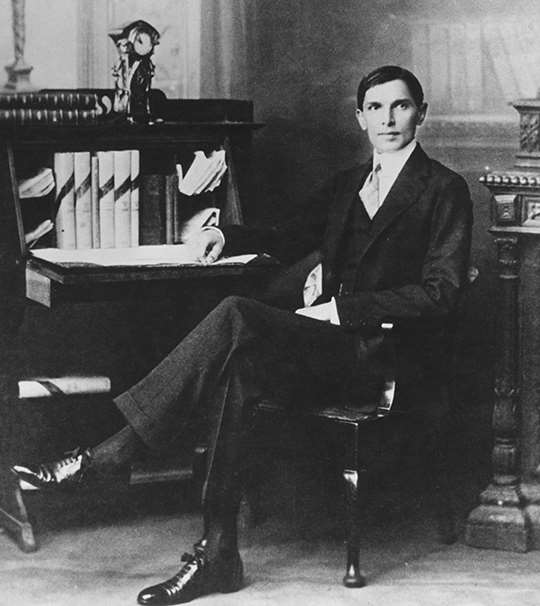

Mohammed Ali Jinnah was the founding father of Pakistan. He was the eldest of seven children born to Jinnabhai Poonja, a merchant, and his wife Mithibhai, and attended the Sind Madrassa then the Christian Mission High School, Karachi, where he failed to excel. He first travelled to Britain when just seventeen years old to take up an apprenticeship with the British managing agency Douglas Graham and Company, marrying his first wife Emibhai shortly before he set sail. Emibhai died just a few months later. Jinnah worked in accounts at the firm’s head office in the City of London. When he arrived in London, he rented a modest room in a hotel. He lived in different places before he moved into the house of Mrs. F. E. Page-Drake as a houseguest at 35 Russell Road in Kensington. This house now displays a blue and white ceramic oval saying that the ‘founder of Pakistan stayed here in 1895.

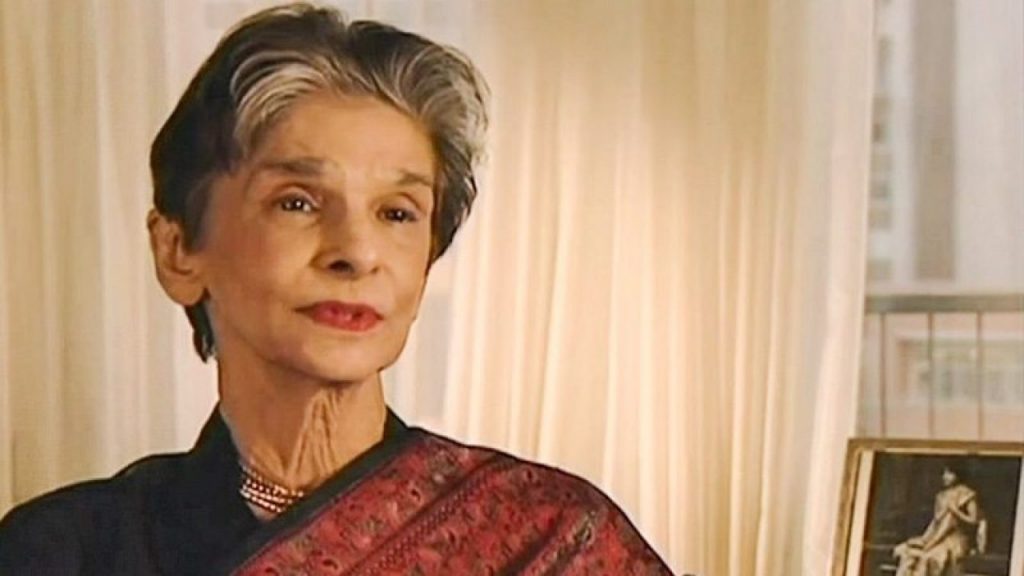

Mrs. Page- Drake, a widow, took an instant liking to the impeccably dressed well-mannered young man. Her daughter however, had a keener interest in the handsome Jinnah, who was of the same age of Jinnah. She hinted her intentions but did not get a favourable response. As Fatima reflects, “he was not the type who would squander his affections on passing fancies”.

On March 30, 1895 Jinnah applied to Lincoln’s Inn Council for the alteration of his name from Mahomed Ali Jinnahbhai to Mahomed Ali Jinnah, which he anglicized to M.A. Jinnah. This was granted to him in April 1895. Though he found life in London dreary at first and was unable to accept the cold winters and gray skies, he soon adjusted to those surroundings, quite the opposite of what he was accustomed to in India. While residing in London, he took to wearing tailored suits and silk ties. Just two or three months after his arrival in England, Jinnah left his apprenticeship to train as a barrister at Lincoln’s Inn. Fascinated by politics, he frequently viewed parliamentary debates from the visitor’s gallery at the House of Commons and was present there to witness Dadabhai Naoroji’s maiden speech in 1893. He studied at the Reading Room of the British Museum, listened to speeches at Hyde Park Corner, visited friends at Oxford, and developed a keen interest in the theatre, even considering a stage career. He was called to the Bar in 1895 and returned to Bombay, India, the following year.

In Bombay, Jinnah joined the Indian National Congress and began to practice law, attaining a position in the chambers of the acting advocate-general, John Macpherson. He first attended the Indian National Congress in 1904, and in 1906 served as secretary to the Congress President, Naoroji, in the Calcutta sessions. In 1909 he was elected to the Muslim seat on the Bombay Legislative Council, and he joined the All-India Muslim League in 1913, becoming its President in 1916 and playing a key role in the Lucknow Pact which brought the Congress and League together on issues of self-government to make a united stand to the British. Jinnah made trips to London in 1913 and 1914 – the latter as chair of the Congress deputation to lobby parliament over their proposed Council of India bill. He also helped to find the All-India Home Rule League in 1916. In 1918, he married his second wife, the Parsee Rattanbai Petit, with whom he had a daughter, Dina, born in 1919.

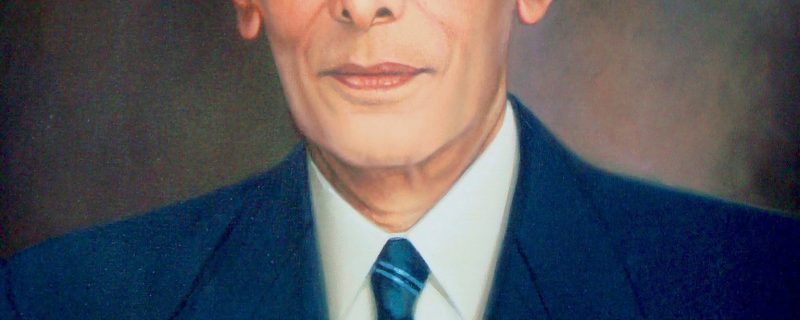

The next few years saw a decline in Jinnah’s political influence and success. In 1919 he resigned from the legislative council in protest against the Rowlatt Acts, and in 1920 he broke with Congress and resigned from the Home Rule League because he disagreed with the increasingly popular Gandhi’s policy of non-cooperation with the British and aim of complete swaraj or self-rule. He remained active with the Muslim League throughout the 1920s, however, and in 1927 negotiated with Hindu and Muslim leaders on constitutional reform in the wake of the Simon Report. In 1930, Jinnah returned to London to participate in the first, abortive Round Table Conference. In his short speech, he represented Indian Muslims as a distinct ‘party’ with their own demands and needs and warned of the urgent need for a settlement that satisfied all of India, including its minorities. At the close of the conference, he decided to remain in England, calling for his sister Fatima and daughter Dina to join him. Despairing of the settlement of Hindu-Muslim conflict, he immersed himself in law, securing chambers at London’s Inner Temple. Jinnah lived in Hampstead during this period. He tried to enter parliament, first as a Labour Party candidate, joining the Fabian Society in an attempt to gain credibility, and then as a Conservative candidate – but he failed on both counts. He also failed to achieve his ambition of practising in the Privy Council Bar. He was invited by Wedgewood Benn to sit on the Federal Structure Committee of the second Round Table Conference, but played a very minor role there, with Gandhi, as the voice of Congress, taking centre stage. During his years in London, Jinnah received persuasive requests from prominent leaders for his return to India to assume leadership of the newly formed Muslim League, including a visit to his Hampstead home by Liaquat Ali Khan and his wife. In 1934, he succumbed to these demands, and returned to Bombay.

Back in India, Jinnah struggled to strengthen the League’s position. In the 1940 League sessions, the Pakistan resolution was adopted by the party. In 1941, he founded the newspaper Dawn which increased support for the League, and in the 1945-6 elections the League was successful in securing most Muslim electorate seats. Jinnah’s concern now was to ensure the best possible outcome for Indian Muslims after independence. He assented to the British Cabinet Mission’s proposals of June 1946 for groupings of Muslim- and Hindu-majority provinces under a weak Indian union government, but later rejected it when Congress refused the idea of parity with the League, and advocated instead the formation of the separate state of Pakistan. On 3 June 1947, Jinnah accepted the Mountbatten plan to transfer power to two separate states. On 14 August 1947, he was appointed as governor-general of Pakistan and set to work establishing a government and restoring order after the horrific communal violence that had accompanied the partition of India. Already suffering from tuberculosis, Jinnah succumbed to the strain of this enormous task and died at home in Karachi just a year the creation of Pakistan. He is remembered by Pakistanis as Quaid-i-Azam, or Great Leader.