How Londinium became London

Report Sadaf Javed

In AD410, the Roman Emperor Honorius sent a goodbye letter to the people of Britain. He wrote, “fight bravely and defend your lives…you are on your own now”. The city of Rome was under attack and the empire was falling apart, so the Romans had to leave to take care of matters back home.

After they left, the country fell into chaos. Native tribes and foreign invaders battled each other for power. Many of the Roman towns in Britain crumbled away as people went back to living in the countryside.

But even after they were gone, the Romans left their mark all over the country. They gave us new towns, plants, animals, a new religion and ways of reading and counting. Even the word ‘Britain’ came from the Romans.

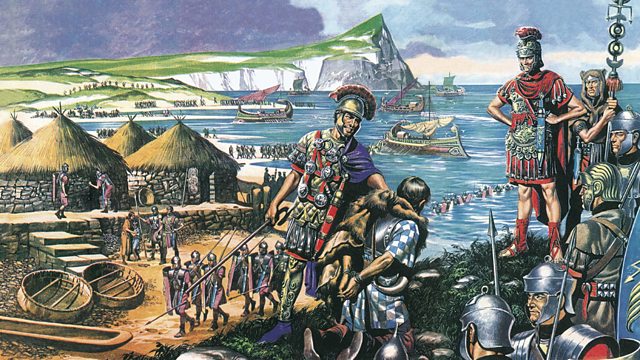

When the Romans arrived in AD43, they introduced new ideas and ways of living to Britain. Watch the video to find out more.

Britain had no proper roads before the Romans – there were just muddy tracks. So, the Romans built new roads across the landscape – over 16,000km (10,000 miles) in fact!

The Romans knew that the shortest distance from one place to another is a straight line. So, they made all their roads as straight as possible to get around quickly.

They built their roads on foundations of clay, chalk and gravel. They laid bigger flat stones on top. Roman roads bulged in the middle and had ditches either side, to help the rainwater drain off.

Some Roman roads have been converted into motorways and main roads we use today. You can still find a few places where the original Roman road is still visible, too.

Bits of Roman road can still be seen. Soldiers and carts used this cobbled road to travel between Manchester and Yorkshire.

Of all the Roman remains in Britain, Hadrian’s Wall is probably the most famous. In AD122 the Emperor Hadrian ordered his soldiers to build a wall between Roman Britain and Scotland. It ran for 73 miles from Wallsend-on-Tyne to Bowness.

Before the Romans came, the native Britons were pagans. They believed in lots of different gods and spirits. The Romans were pagans too, but they didn’t believe in the same gods as the Britons. They let the Britons worship their own gods if they were respectful of the Roman ones too.

Christianity arrived in Britain during the second century. At first only a few people became Christian. When Christianity started to get popular, the Romans banned it. Christians refused to worship the Roman emperor and anyone who was caught following the new religion could be whipped or even executed.

By the beginning of the 4th century, more and more people were following Christianity. In AD 313 the Emperor Constantine declared that Christians were free to worship in peace. By 391, Christianity was the official Roman religion, but pagan beliefs were still popular in Britain.

A cartoon image of the Roman Emperor Constantine sitting on a throne.

Constantine was the first Roman emperor to allow Christians to worship. He later became a Christian himself.

Language, writing and numbers

Before the Romans came, very few people could read or write in Britain. Instead, information was usually passed from person to person by word of mouth.

The Romans wrote down their history, their literature and their laws. Their language was called Latin, and it wasn’t long before some people in Britain started to use it too. However, it only really caught on in the new Roman towns – most people living in the countryside stuck to their old Celtic language. We’ve still got lots of words and phrases today that come from Latin. Words like ‘exit’, which means ‘he or she goes out’, and ‘pedestrian’, which means ‘going on foot’.

Our coins are based on a Roman design and some of the lettering is in Latin. Written around the edge of some £1 coins is the phrase ‘decus et tutamen’ which means ‘glory and protection’.

Some clocks today still use Roman numbers. Can you tell what the time is?

How did the Romans change towns?

The Romans introduced the idea of living in big towns and cities. Roman towns were laid out in a grid. Streets criss-crossed the town to form blocks called ‘insulae’. In the middle was the ‘forum’, a big market square where people came to trade.

After the Romans, the next group of people to settle in Britain were the Anglo-Saxons. They were farmers, not townspeople. They abandoned many of the Roman towns and set up new kingdoms, but some Roman towns continued to exist and still exist today.

If a place-name has ‘chester’, ‘caster’ or ‘cester’ in it, it’s almost certainly Roman (for example, Gloucester, Doncaster and Manchester). The word ‘chester’ comes from the Latin word ‘castrum’ which means ‘a fort’. London was a Roman city too, although they called it ‘Londinium’. When the Romans invaded, they built a fort beside the River Thames. This was where traders came from all over the empire to bring their goods to Britain. It grew and grew, until it was the most important city in Roman Britain.

Romans Roads

How, where, and why a vast network of roads was built over the length and breadth of Roman Britain.

Following the Roman invasion of Britain under the Emperor Claudius in AD 43, the Roman army oversaw the rapid construction of a network of new roads. These served to link the most important military places in the new province of Britannia.

Roads allowed troops to move efficiently from ports such as Richborough and Dover in Kent, and enabled officials and messengers to travel swiftly, using the imperial communications system (later known as the cursus publicus). Many of the early roads served to link key pre-existing settlements such as Colchester in Essex and Silchester in Hampshire. These became Roman towns, and important centres for the developing Roman administration.

Core Values

The structure of Roman roads varied greatly, but a typical form was an agger, or bank, forming the road’s core, built of layers of stone or gravel (depending on what was available locally). In areas of soft ground the road might be built over timber piles and layers of brushwood. The core of the agger would be covered with a layer of larger stones, if available, with the upper surface being formed from layers of smaller stones or gravel. The full ‘road zone’ could be defined by ditches set some distance from the road, providing drainage and possibly space for pedestrians and animals.

The width of roads varied from about 5 metres to more than 10 metres. Some were far less well constructed than roads of the type described above. Less than half a mile south of the Roman town of Cataractonium (Catterick, North Yorkshire), the main Roman road north to Hadrian’s Wall, Dere Street, consisted of nothing more than successively wider spreads of gravel over a shallow agger.

As Roman power extended across England, so did the road network. Eventually a system was created that linked the south coast ports to Hadrian’s Wall and even reached into what is now Scotland. The Roman Road known as the Fosse Way linked the south-west with Lincoln, having demarcated a temporary frontier in the late AD 40s when the Roman army paused before pushing further north and west. The Stanegate, which stretched from east to west between Corbridge and Carlisle, similarly marked a frontier before Hadrian’s Wall was built to the north of it in the AD 120s.

Roads to the Sea

The roads built by or for the army not only served to link forts and towns as they developed but were also essential for trade. Moving goods by water was cheaper than overland transport, however, so the road network linked with the sea and inland ports. Many of the supplies required by forts, such as Housesteads and Birdoswald on Hadrian’s Wall, would have arrived via the seaports of Carlisle and South Shields. Their journey may have continued via rivers before being completed by road. Nonetheless, the Romans did move goods long distances by road – at least when there were no obstacles to doing so. A writing tablet from Vindolanda fort near Hadrian’s Wall records delays in receiving supplies of hide from Catterick because of the poor state of the roads.

But away from the engineered roads built by the army, much of the population would have relied on tracks that wound between fields, often following routes established centuries before. Many army supplies, as well as goods that were traded in towns, would have started their journey on these ancient tracks before reaching the major roads.